Catching a glimpse of Jalisco’s entrepreneurial past

Hacienda La Escoba is a property of major historical significance in the municipality of Zapopan, in the greater metropolitan area of Guadalajara. At one time, it played an economically important role in the Jalisco region as one of the first industrial production centers of yarn and fabric. Structures erected there included employee housing, an aqueduct, and production facilities, all in the neoclassical tradition. While some of those original structures are still standing and have been at least partially restored, only ghostly vestiges remain of the rest.

These days, the area is in private hands and its various spaces are available for rent, to serve as the scenes of festivities such as weddings. Generally speaking, La Escoba is also just a beautiful place to visit and stroll through. If you’re looking to host an event or simply walk the expansive grounds and get a sense of the splendor of the former land-owning business class of Jalisco, Hacienda La Escoba can definitely provide that. A visit here can make you feel as though you’ve pleasantly slipped back in time.

The Logistics

Directionally speaking, the hacienda is located to the northwest of Guadalajara proper along the highway that would ultimately take you all the way to Jalisco’s border with the Mexican state of Zacatecas to the north (if you were to follow it that far). From the entrance on that highway, a bit of a drive remains to get you onto the main grounds where the church and other structures and spaces are situated.

Getting there is most easily accomplished by hiring a car, such as an uberX, or renting one from a reputable car rental agency. If you have local friends with a vehicle, maybe they can give you a lift, or perhaps you can utilize ride-sharing like BlaBlaCar. Personally, I was fortunate enough to get rides with friends out there and back in order to attend a traditional Mexican wedding. Expect to spend over an hour or hour-and-a-half driving there. It can be a bit of a haul, especially when you factor in traffic and so on starting from inside Guadalajara.

The prospect of visiting by public bus is not appealing. I’m a perpetual fan of using the local bus system wherever possible, but so far as I could tell no buses go near the entrance to the hacienda, never mind inside of it.

What to Expect

As previously mentioned, I attended a traditional Mexican wedding that was held on the grounds of Hacienda La Escoba. This meant a lengthy religious service inside the restored, rather wonderfully spartan church, followed by snacking and mingling in the neighboring square where we all soon thereafter witnessed the couple’s civil ceremony.

We all then moved to a forested area on the grounds with some structural remnants where the socializing, drinking, and snacking continued. Eventually, we guests were seated for dinner and performers sung arias for us all while we dined. Dancing and festivities and more drinking later took over, briefly interrupted by what can only be described as a midnight breakfast service. And then more partying. It was a marathon.

The grounds are peaceful and lush and make one feel far away from it all, while the old bones of the hacienda as a whole are enchanting and intriguing. It truly was an exceptional place to spend the afternoon and evening celebrating the couple’s matrimony. One can imagine this to be a special place to throw an anniversary party, celebrate a graduation or retirement or singular lifetime event, host a religious ceremony, or really just wander about.

So far as I could tell, restoration efforts were in the advanced stages, if not already completed. Some walls had purposely been left to romantically deteriorate and be overgrown by vegetation, while others had been modernized by being wrapped in or melded with glass and metal to create new enclosed spaces to host events in.

The property’s lake, fed by a channel of the Santiago River, is picturesque. Prior water contamination has supposedly been addressed. Massive reforestation has been undertaken and nurseries have been created. Management claims their efforts have greatly benefitted the local environment and ecosystem, which are now not only stable but much improved and provide a sanctuary for birds and other animals. Ecologically-speaking, the impact looks to have been positive and the visual appeal is difficult to deny.

The Spaces

One can reserve up to five spaces:

- The Aqueduct Patio is an open patio defined by part of the original aqueduct of adobe and stone. It has a capacity of 800 persons.

- The Main Hall is across the way from the church near the hacienda’s inner entrance. Its outer walls are archways of stone and glass. It can accomodate up to 2,000 people.

- The Hall of Ruins sits the deepest inside the hacienda’s property. With room for a more modest 350 people, it might also be the most intimate. This building used to house the factory machinery and its restoration was supposedly supervised by the INAH, or Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia (National Institute of Anthropology and History), as La Escoba has been designated a national heritage site.

- The Church is beautiful in its stark simplicity, with very little in the way of distracting elements inside or out. There is no stated capacity on the hacienda’s official website, but the wedding I was present at had several hundred guests in attendance and we all fit comfortably. Next to the church is a large square lined on one side with an arched colonnade. A gazebo is situated prominently right about in the middle of said square.

- The Esplanade with View of the Lake is pretty much smack on the lakeshore on slightly raised ground. Like the the main hall, it can accommodate up to 2,000 people.

La Escoba: The Backstory

First things first: Did I mention I have a History undergrad? Consider yourself forewarned…

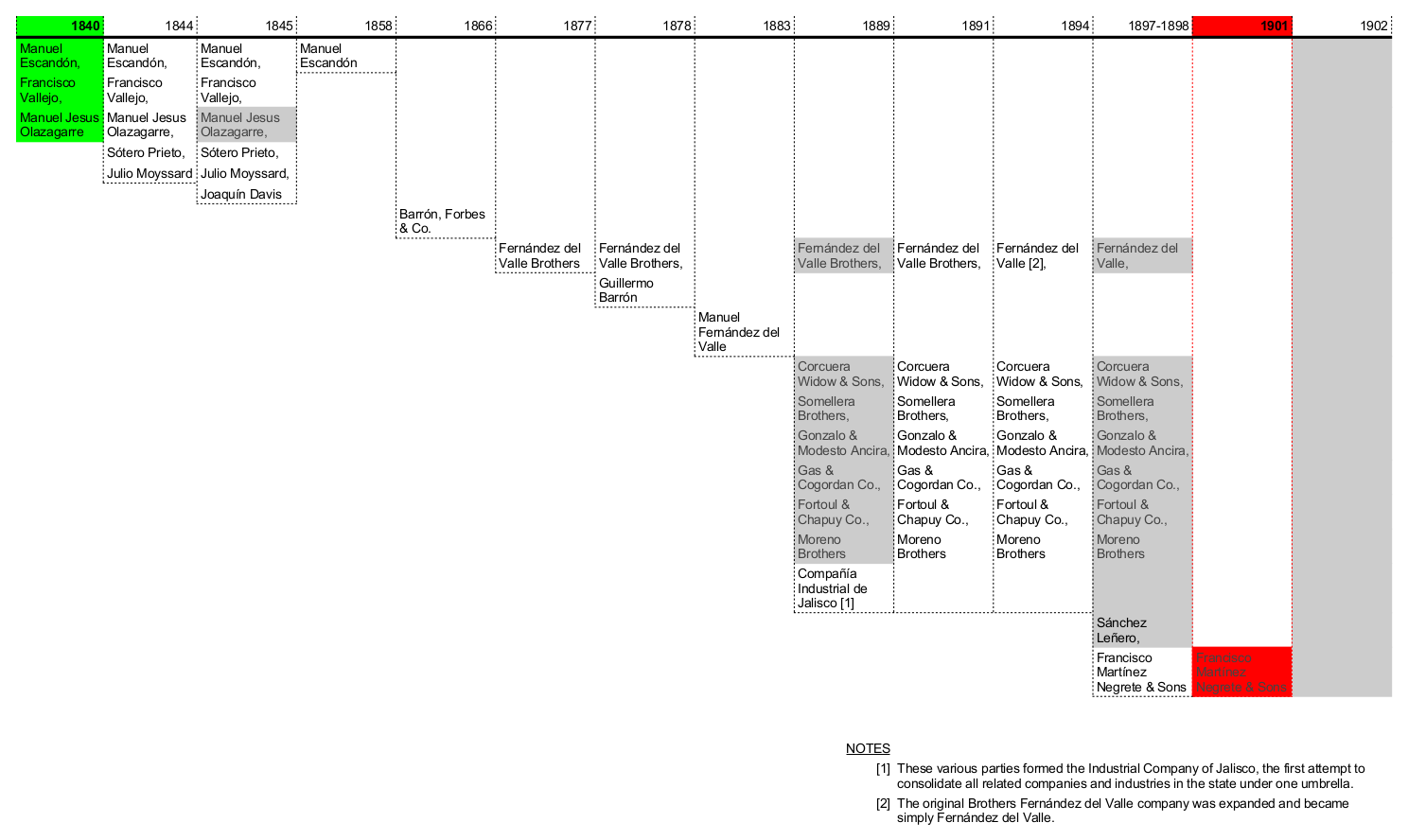

Sources indicate that the property known today as Hacienda La Escoba actually began on another property called Hacienda La Magdalena. The cotton yarn and fabric company – from whose name the hacienda’s current name was derived – was born from a business partnership primarily between the owner of La Magdalena, Don Manuel Jesús Olazagarre, and Dons Manuel Escandón and Francisco Vallejo, although one source indicates that additional associates would join the operation as minor providers of capital later on.

Originally from Panama and perhaps of Basque ethnicity, Olazagarre put up some of La Magdalena’s land. Escandón, from Mexico City, contributed the vast majority of the capital, for his part. He was the principal owner of the new enterprise. Vallejo, possibly also from Mexico City, put up a relatively small portion of the total investment to help get the operation started.

La Escoba, the company, was founded in 1840, on paper anyway. As director and part owner, Olazagarre was charged with construction of the facilities and administrative duties, and would hold final decision-making power over every aspect of the firm (the acquisition of machinery being the sole exception).

By 1842, construction on an isosceles-triangle-shaped portion of La Magdalena property was underway on a variety of structures, including the main building, a dam and aqueduct, the director’s house, storehouses, and rooms for machinery operators. Olazagarre also oversaw the installation of machinery equipped with some two thousand moving spindles, and the supply of enough raw cotton material sufficient for the first two months of production.

Over the next many years, the going concern would grow and have an increasingly sizeable impact on the regional market, all while business partners came and went and ownership changed hands a few times. For instance, new financial contributors, Sótero Prieto and Julio Moyssard, came onboard in 1844. The following calendar year, an associate by the name of Joaquín Davis joined in while Olazagarre renounced his directorship.

What’s more, with Olazagarre’s retirement, it was agreed that the land, water, and material directly pertaining to La Escoba become the permanent property of La Escoba’s business group and cease to belong to Hacienda La Magdalena. That group would have first dibs on purchasing any neighboring property Olazagarre owned should he wish to sell any of it, and he was prohibited from establishing any new companies on his own property.

By 1858, Manuel Escandón was the sole owner of La Escoba and would remain so until selling it all to Barron, Forbes & Co, in 1866. Eventually, the Fernández del Valle Brothers would take over, first on their own in 1877 and then in association with other investor-proprietors in 1889.

During that same year, La Escoba even briefly found itself in the hands of the Compañía Industrial de Jalisco (Industrial Company of Jalisco). This was a short-lived entity formed by multiple interested parties – Viuda e Hijos de Corcuera (Corcuera Widow & Sons), Somellera Hermanos (Somellera Brothers), Gonzalo & Modesto Ancira, Gas & Cogordan Co, Fortoul & Chapuy Co, and the Moreno Hermanos (Brothers Moreno) – with the express purpose of consolidating ownership of all factories related to textiles and paper in Jalisco, especially those near Guadalajara, in its hands. It represented the first attempt at industry domination of its kind in the area, and relied on capital fronted by Mexican, as well as Spanish and French, nationals.

In spite of the involvement of so many different parties over its productive life of roughly 60 years, it could be said that La Escoba was somewhat consistently in the care of just a few, according to the historical record. After all, Escandón was at the helm for the first 26 years. Barrón, Forbes & Co. managed the operation for some 11 years thereafter, followed by the involvement of members of the Fernández del Valle organization for another 20 years or so.

The next passing of the baton, which began in 1897, would prove to be the factory’s last, as well as its strangest. The story goes that an “unofficial” property swap was arranged between the former Industrial Company of Jalisco participants and Francisco Martínez Negrete & Sons, one of the region’s most affluent family organizations with multiple business interests (the range of which some might consider even too diverse in nature). La Escoba, pasture in Tesistán, and a factory named Río Blanco were exchanged for haciendas San Francisco and Santa Ana, both located in Tizapán El Alto. Things were notarized and made official in 1898.

Not yet three years into their new roles as La Escoba owners, Francisco Martínez Negrete & Sons went bankrupt, losing not only the entire enterprise but all of the other business entities under the family’s control. According to court documents dating back to early 1901, the house of Francisco Martínez Negrete had hit the liquidity wall and could no longer meet the numerous demands of its creditors.

Why or how the family reached this point is unclear. There is evidence that during the Porfiriato, or the years during which General Porfirio Díaz was President of Mexico, economic inequality was exacerbated, placing the country and its people under ever-increasing strain. The family’s bankruptcy took place toward the end of this period, not quite a decade before the Mexican Revolution broke out in an obvious way.

Whether that growing discontent had something to do with it; or whether it was the possibility that the Martínez Negrete family had simply overextended themselves given the sheer number and/or variety of going concerns it managed and owed money against; or whether there was something else at the root of it, it can’t be said with certainty. What is clear now is that La Escoba would apparently never churn out another spool of yarn again. Its machinery ended up in other factories in the region, namely Atemajac and La Experiencia, and its inventories were otherwise liquidated.

In some cases, those inventory items were of considerable quantity and value. For example, over 118k kilograms of cotton priced at almost $70k MXN (in 2011 pesos) remained. An assessment by one scholar puts the total value of the company at that point in 1901 at over $418k MXN (again in 2011 pesos), with maybe half of that made up of buildings and machinery.

The following decades of the 20th century are a bit murkier, as far as online sources of information go. There is mention of a “group of tapatíos” purchasing La Escoba and utilizing it for “social” purposes. Then between 1910 and 1914, years during which the Mexican Revolution was in full swing, the property appears to have suffered looting and damage caused by fires.

Fast forward to the years 1926-1929 and the Cristero War (La Cristiada), an armed conflict between church and state that saw the Mexican government attempt to legislatively secularize society and diminish the power of the Catholic church and its affiliates. One finds out that fighters in the rebellion somehow utilized La Escoba during the conflict, as Jalisco was a serious hotbed of what some would term the last substantial peasant uprising in the country’s history to date.

Then…nothing, it seems. Without some serious further digging through library assets or legal or public records, I don’t know anything beyond what the official Hacienda La Escoba website relates. The current owner, whoever that is, took possession of La Escoba in 1995 by some means. How, and from whom, they acquired it is also not revealed.

Whatever the identity of the involved party, restoration and preservation of this significant architectural, industrial, and cultural legacy once occupied by former representatives of Jalisco’s entrepreneurial class have been, and are, the names of the game. There is little reason to doubt that the property was in disrepair by 1995. However, all the rejuvenation targets explicitly listed on the website, including the Big House, the church, a portion of the factory, the looms room, and the aqueduct, appear to have received some TLC that I’m sure was overdue.

All the better for those looking to have an even more memorable time in the greater Guadalajara area. Make this unique side of Jalisco momentarily yours.

For more photos and further details on La Escoba, including on how to reserve space for an event, see the following references for this article:

- Hacienda La Escoba website. (2013). Retrieved from <http://www.haciendalaescoba.com/>.

- Lizama Silva, Gladys. (2011, January). “Inventario de la fábrica textil La Escoba, Guadalajara, Jalisco, 1901“. Retrieved from SciELO (Scientific Electronic Library Online) México <http://www.scielo.org.mx/scielo.php?lng=es>.

- Trujillo Bolio, Mario A. and José Mario Contreras Valdez. (2003). Formación empresarial, fomento industrial y compañías agrícolas en el México del siglo XIX. Retrieved from Google Books <https://books.google.com/books?id=YANoFKy4QHsC&source=gbs_navlinks_s>.