Get your soak on in Idaho

Having returned from Costa Rica and the highly touted Tabacón hot springs there not long ago, I’m compelled to make the case for an amazing domestic gem of Idaho’s State Foundation, Lava Hot Springs (LHS), located in the Southeastern corner of the US state of Idaho. Not all hot springs are created equal.

Worlds apart, one might wonder what the hell I’m doing comparing Tabacón and LHS at all. And really, a side by side comparison is not my objective here. I’ll reserve my synopsis of Tabacón for a separate article. Suffice to say, though, that my experience there, while grand in its own right, only served to heighten my enthusiasm for LHS.

The story

The town where the source is located is also named Lava Hot Springs, and it is unclear as to which entity derived its name from which. It is situated on a stretch of Highway 30 connecting Highway 15 to the west with such places as Soda Springs and, eventually, Highway 80 inside Wyoming, further to the east.

Generally speaking, the landscape and area are mountainous, with snowfall and freezing temps in the winter. The pools are nestled against a cliff face above which runs a road and railroad tracks. When the train passes by, especially at night, it lends a romantic western mystique to it all.

Tarps overhead covering parts of four of the pools protect you somewhat from inclement weather, while the wonderfully warm water does the remainder of the job. Note that no refunds are offered due to weather conditions, and you will get yanked out of the water during a lightning storm. If the storm looks like it’s going to pass and you’re part of a group, you can hang out in the family locker room together and wait it out, or they will hand out wristbands if you want to go into town for a bit and come back later. Shucks, grab a burger and a beer at the Blue Moon while you’re at it.

Before you go, you can take a look at their webcam. Otherwise, with the exception of a fullon lightning storm, where else would you rather be during a snow, hail, or rain storm than safely and softly steeping in 102-112°F water graciously and rather endlessly offered up by the earth and its crust? It’s a never-ending cup of tea, and you’re the tea bag.

What’s more, its a healthy cup of tea. First off, the water, constantly cycling through at a rate of at least 2-2.5m gallons daily on its way to being diverted into the Portneuf River, is never treated with chemicals such as chlorine; with such flow from the source, it’s unnecessary. At that rate, all other things being equal, it takes approximately two hours for pools to empty and refill. Put another way, the pools have “new” water every couple of hours.

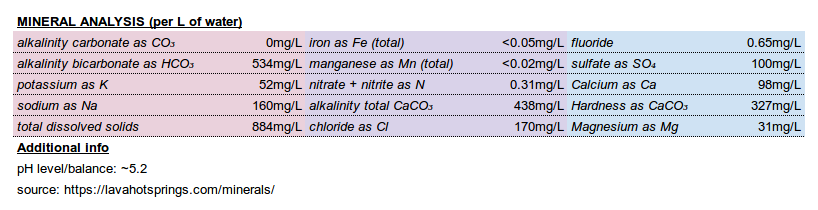

Next, all that water is loaded with mineral content. One chemical analysis provided by the organization at the hot pools lists the following values per liter (L):

At the end of it all, you don’t walk away stinking of anything. Not only is chlorine not utilized, but there’s virtually no sulfur present in the water, sparing you the smell of cooked eggs.

And there’s a pool for everyone. It is not a one-size-fits-all situation. Five pools are fed by one source, getting progressively cooler the further away they are from that source, which is captured and directed to the rest by the hottest pool (and the original) in the northeastern corner of the property as you enter. That one starts at approximately 112°F (or hotter in parts, to be honest).

From there, the temperature falls to 110°F at the near side of the next big pool, gradually falling to 106°F as you wade through to the far side of that one.

The two smaller pools in the entire place, situated between this large one I just mentioned above and the third of the big ones off on the other side of the area (and the coolest in terms of temp), run at approximately 105°F. Finally, that third biggest pool furthest from the source pool drops to 102°F.

As if this place weren’t stellar enough, the price of entry is low on account of it being in public, or government, hands. Admission is only $6 on weekdays for a one-time visit (less for children and seniors), and $8 Fridays-Sundays plus holidays. Many places like this throughout the United States and the rest of the world have been privatized. Companies have taken what nature has provided and converted the locales into high-cost, exclusive destinations.

(In comparison, for a full day at Tabacón you will pay $105 USD. Yes, that gets you a couple of buffet-style meals as well as all-day access to the water in a beautiful setting, but still, that’s expensive.)

Not that the LHS area only sports the hot pools. At the entrance to town, one can find the massive Olympic Swimming Complex, featuring a “free-form” olympic-length swimming pool, water slides, diving towers, and indoor aquatic center, among other amenities. Between this and the hot pools, you have gardens, picnic areas, and lawns, and an entire town ready to host you with hotels, restaurants, shops, you name it. The whole lot of this slice of paradise in southeastern Idaho is tucked inside a cove wedged between the Rockies’ western flank and the Wasatch Range stretching south.

Check their hours and rates, which include prices for one-time, all-day, child-adult-senior, and multi-day and family pass prices, and plan your visit. They are open all year around and almost every single day. No towels or swimsuits, no problem – you can rent them there. Just show up with your fine selves…

Background info & additional resources

While preparing this article, I reached out to the Shoshone-Bannock Public Relations Department for comment in the hope that I might be able to clarify some of the historical details and current perception of the town and its commercial enterprises. Unfortunately, I did not receive a response prior to the publication of this piece.

How LHS came to be in the hands of the Idaho State Foundation, and not still in the hands of the Shoshone-Bannock peoples, is a bit murky. Perhaps this is how some wished it to be, if you know what I mean, as is the case with many misdealings with First Nations peoples by the United States government and new waves of “settlers” over time.

What records I could procure indicate that the land and attendant water resources that comprise LHS today were actually originally part of the Fort Hall Indian Reservation as established by the Fort Bridger Treaty of 1868. However, the “surplus lands” were “sold” to the United States government for a princely sum, at least on paper, through an agreement with the Shoshone-Bannock peoples toward the end of that century.

In congressional documents, it is referred to as a treaty dated 1898, to be specific. With that agreement ratified by the US government at the start of the 1900s, the land worked its way rather quickly through the system and into the hands of the state of Idaho only a couple of years later via the Presidential Proclamation of May 7, 1902. In that proclamation, the land was ceded to the state “for public use”.

By 1911, pool facilities were being funded and constructed. Thereafter, the area saw further development and growth on into recent years, as well as some setbacks such as flooding of the Portneuf, business bankruptcies, and fire damage.

Today, locals, visitors from all over the world, and First Nations peoples regularly converge on ‘PohaBa,’ or land of healing waters. While one does indeed feel healed by the water, I personally have found it difficult not to wonder about the potential sleights of hand, harmful actions, and damaging treatment that may have created the circumstances leading to the current state of affairs and the land becoming a public commercial enterprise in the hands of the state of Idaho instead of land left alone for the benefit of all.

If I learn more, I’ll be sure to update this article.